WWII: Rijkswerkkamp De Rips (verdwenen) | De Rips

Contents

1 Colourful procession of residents national labour camp

1.1 Summary

1.2 Provision of work

1.3 Unemployment camp

1.4 Amsterdam residents

1.5 Chinese

1.6 Traders

1.7 Revolt of the Chinese

1.8 No swearing

1.9 Father Smeets

1.10 Tuberculosis

1.11 Departure of the Chinese

1.12 British occupation

1.13 Canadians in the Ripse camp

1.14 Christmas with the Canadians

1.15 Again in Dutch hands

1.16 Soldiers again?

1.17 War volunteers or N.S.B. personnel in the camp

1.18 War volunteers

1.19 To the Dutch East Indies

1.20 Conscripts

1.21 Gaffs, Boils and Feasts

1.22 The provisional end of the Camp

1.23 Conscientious objectors

1.24 Notes

Summary

Rijkswerkkamp De Rips, popularly called the "Chinese Camp," wa…

Contents

1 Colourful procession of residents national labour camp

1.1 Summary

1.2 Provision of work

1.3 Unemployment camp

1.4 Amsterdam residents

1.5 Chinese

1.6 Traders

1.7 Revolt of the Chinese

1.8 No swearing

1.9 Father Smeets

1.10 Tuberculosis

1.11 Departure of the Chinese

1.12 British occupation

1.13 Canadians in the Ripse camp

1.14 Christmas with the Canadians

1.15 Again in Dutch hands

1.16 Soldiers again?

1.17 War volunteers or N.S.B. personnel in the camp

1.18 War volunteers

1.19 To the Dutch East Indies

1.20 Conscripts

1.21 Gaffs, Boils and Feasts

1.22 The provisional end of the Camp

1.23 Conscientious objectors

1.24 Notes

Summary

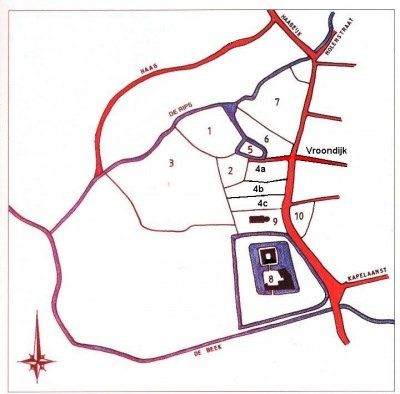

Rijkswerkkamp De Rips, popularly called the "Chinese Camp," was built starting in late 1940 and was initially intended to house unemployed people who were put to work from the National Works Administration. (not to be confused with D.U.W. Department of Works). It consisted of wooden buildings, such as house with large kitchen and associated storage room, large canteen and 4 pieces of living-sleeping barracks with a 12 open latrines. It could house 192 people. In 1941 it housed about 120 Chinese Boatmen who could no longer sail from the blockaded port of Rotterdam. They were put to work in the Ripse woods and reclamations in the Peel. At the end of the war it was a command post and field hospital of the British land and air forces. After the war it was a training camp for O.V.W. men. (war volunteers). Here they received basic training to be sent to the Dutch East Indies. In short, the motley procession of residents was much longer. You can read this below or you can view the shorter info panel version.

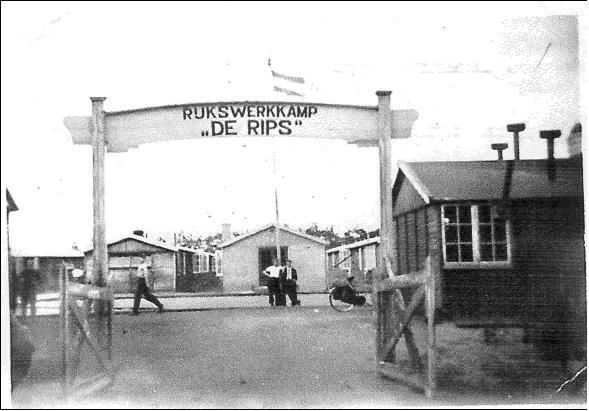

Replica of the entrance gate with the info panel with explanation

By: Bernard Ploegmakers and Ruud Wildekamp

Worker Relief De Rips. The Reich Labor Camp during the Second World War.

In the 1930s there was great unemployment among the population of our country. To assure himself and his family of a small income, the unemployed had to rely on a benefit. He had to report daily to the Social Affairs office of his municipality. As proof that he had reported, he received a stamp on his unemployment card. A full card entitled him to an allowance of eleven guilders per week. An unemployed person could be designated for employment under a workfare project. Usually this consisted of unskilled spit and digging work. The unemployed benefit then lapsed but in return the unemployed person received a wage for the service rendered. This could amount to about eighteen guilders per week. Due to austerity measures of the Colijn government, in the early 1930s, the unemployed benefits were greatly reduced. In the summer of 1934, this led to the so-called Jordaan riot in Amsterdam in which five people were killed.

To compensate, municipalities could apply to the Ministry of Social Affairs for subsidies for local employment projects. The local unemployed were then placed on these and sometimes unemployed people from a neighboring municipality. A municipality could, if it had a shortage of its own unemployed, apply to the Ministry of Social Affairs to convert a municipal project into a central government subsidized employment project. Projects by companies or individuals could also qualify. This meant that unemployed people from outside the municipality were